CD PROJEKT. NO FILTER - vol. 2

Episode 01: High-flyers of CD Projekt. From the communist Poland to the world’s gaming valley

Episode 03: “I don’t sleep, because I’m a Red”. This is what CD Projekt looks like with rose-coloured glasses off

Episode 04: Bile instead of gold. CD Projekt’s seven cardinal sins

Episode 05: A wolf pack of millionaires rule CD Projekt. Still, their history is not all rainbow roses

Fifteen. As many as this American law firms specializing in class action lawsuits felt blood. From New York to Los Angeles, the lawyers perfectly know where their chances are for a courtroom fight yielding a substantial profit. Even if they never played the games and not necessarily know where exactly Warsaw is situated.

And the prospects for a fight brighten where people lose their money.

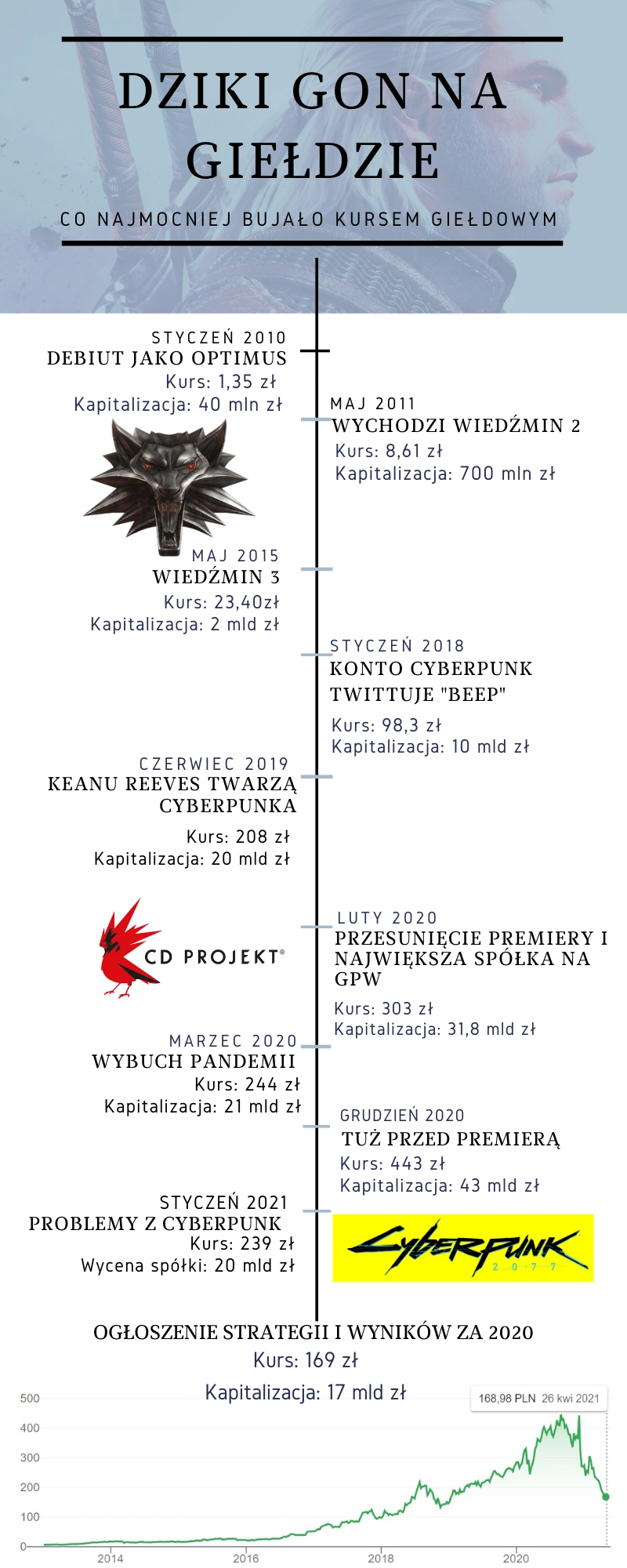

February 2020. In three weeks Europe will be facing lockdown. Still, for the time being, the news on the China virus do not raise such emotions. But the media get carried away: With a value of almost 32 billion zloties [8.2 billion dollars] (based on stock market price), CD Projekt is more valuable than Orlen, the very state-owned giant.

The stock exchange is going crazy about CD Projekt for the whole of past year. In August, the price per share jumps up to 462 zloties, which is, almost by 200% year-over-year. Slight declines follow, but before the very release of “Cyberpunk 2077” that had been awaited for eight years, the price is jacked up to 464.8 zloties.

Except that instead of a great success, “Cyberpunk 2077” sets off a wave of criticism and players’ complaints. Sony withdraws it from its PlayStation Store, and the company's price plummets by more than 40% over two weeks. Hoping for further gains, the investors are outraged. And the more outrage and the more criticism towards “Cyberpunk 2077”, the more American lawyers well-trained in class lawsuits see a great opportunity to fight for damages.

The trading floors have seen more than that already. Except that the business story of CD Projekt is something more than a story of a technological giant with problems on the trading floor. The truth is, the company’s expansion reflects the entire history of Polish capitalism of the last quarter of a century.

“I will swap games” - reportedly, such was the announcement made by some Greek guy in “Your Sinclair”, a British newspaper, that Marcin Iwiński, a the then teenager, stumbled upon. He wrote a letter: “I don’t have any games, but maybe you would like to share yours”. And he inserted two floppy discs - one for the game, and the other for the Greek guy for all the trouble. Much to the teenager’s surprise, the guy did send him a few games. All of a sudden, the novelties from abroad make Iwiński and his friend, Marcin Kiciński, prominent figures of the Grzybowska bazaar.

Be it just a colourful legend, it ideally epitomises the philosophy of a company which became the greatest prodigy of the tech industry in Poland. A philosophy of: the chances much as being negligible, it is still worth trying.

Today’s name for such companies CD Projekt was back in the 1990s is start-ups. They have their incubators, business angels, investors, investment rounds, marketing budgets and some grand plans to conquer the world. The small firm which had just been done pirating at a computer bazaar had all of this, too. Except that it had all of this for those times: Poland swept up in capitalism, pop-culture and the colourful West.

A few years spent on a computer bazaar on the school grounds in Grzybowska Street was like the best entrepreneurship incubator ever. It also gave the high-flyers of computerisation all that the business people of the 1990s needed. “They knew the market, the people, they had savings from the bazaar dealings, because you could make some good money there. Plus, they came from nice background. Those were not poor families, not like ‘from rags to riches’. Staszek, Marcin’s dad, was a film maker who would travel the world. Anyway, Marcin himself as a teenager flew to the US, and back then that was SOMETHING”, recounts Ryszard Chojnowski, a games translator and one of “The Witcher” project managers.

At the beginning, a typical start-up seeks money among the famous 3xF, which is friends, fools and family. Same goes for CD Projekt. Beginning 1994, Michał Kiciński sold an inherited land plot in Kobyłka near Warsaw for 10.000 dollars. It was loads of money for those days. All of the money will fuel the new business.

Friends from the demoscene times help the firm with promotion. “Secret Service”, today’s iconic computer magazine, provides the strongest support for the newly registered firm at that time. “It is from ‘Secret Service” in mid-1990s that I heard about them for the first time. They published a big advertisement. At that time, it was the most prestigious magazine, so an ad there was really something”, recalls Marcin Kosman, a journalist and an author of “Not Only The Witcher. The History of the Polish Computer Games”.

Gambleriada, 1994 rok. fot. materiały prasowe CD Projekt

Connections come in handy also when :”Gambler”, yet another important title on games, starts organising Gambleriada, which was huge and, for the mid-1990s, very professional fairs. The baby firm of Iwiński and Kiciński gets the most exposed stand there. Connections translate into substantial business.

One of the first contracts is made with American Laser Games, a games producer which no longer exists. And then again, that was due to, as we would nicely put it today, “networking”. They were put in touch by Don Hira, a Hindu wholesaler, Kiciński’s supplier from the days of Grzybowska bazaar. Iwiński recalls that they ordered 40 CDs of some game once, because Don Hira convinced them it was great fun. For the players it was rubbish, and a challenge for the company, because the CDs had to be sold anyway. They would be palming off 40 copies of the game for over three months until they could breathe a sigh of relief.

Breaking through was not easy. Indeed, Iwiński already had connections among the European players thanks to the demoscene. But it is one thing to know like-minded enthusiasts, and to know the right people in big company, yet another. “The only chance was to show up at the fairs, go to the stand of those big companies and attempt to catch up with the president or another business decision maker. You had no access to their emails yet, LinkedIn was non-existent. On the other hand though, at that time the industry would still give small start-ups a warmer welcome”, recounts Kosman.

What was the greatest problem also turned out to be the most helpful: no one in the world would take the Polish market seriously. Indeed, a new copyright law had been in force since 1994. Still, the snapshots of consecutive police raids seizing boxes and sometimes even the whole pallets of pirate CD with games and programmes would crop up in the media over and over again. And when it comes to the revenues from game sales, the top deck of Jarmark Europa [Europe Bazaar - a bazaar on the top deck of Warsaw's biggest sports stadium] could easily compete with the entire Empik network, Poland's largest network of shops with the press, books and multimedia. And the Polish market knew that. Producers from abroad knew that, too, and they perceived Poland as an exotic chip off the ex-communist world, unworthy of interest.

If the market was negligible, the local distributors stood a greater chance of pulling it off. CD Projekt soon made its way to become one of the most important companies on the market. “It was a time when IM Group was still in business (then transformed into Cenega). LEM, which is, the then Licomp Empik Multimedia, and a number of minor distributors. But the strongest competition was among those three. The status quo achieved in the late 1990s continued through to the first decade of 21st century”, says Michał Bobrowski, for 20 years in the gaming industry, including a board member of GRY-Online SA for a decade.

“If a Polish company wanted to localize, that is, translate games into Polish, let them do it”, agreed other foreign studios, such as Acclaim, Blue Byte, Interplay and finally Blizzard. Except that let them do it on their own, no assistance provided.

“Cottage industry, that is. The official distributor received no support from the producer, as they did not care about the Polish market yet. So, you had to extract the text from the game. By the sweat of his brow, Maciej Marzec would often break the unbreakable security. He would extract the texts, they would be passed on to me, and the sounds to the recording studio”, recalls Chojnowski, who would at that time translate for CD Projekt not only descriptions on the boxes and manuals, but also the descriptions and dialogues in the very games.

Demoscene connections would come in handy all the time. Particularly those with hackers, as you needed reverse engineering to release games fit for the Polish market. Or, to put it simply: you had to break into the game yourself. “At the Grzybowska bazaar, they met the famous CSL, one of the first Polish hackers, just to give you an example. And years after, already as CD Projekt, they used his services”, recounts Chojnowski.

CSL, which is, Konrad Olszewski, has been for 20 years working at Etop (which identifies on its site CD Projekt among its clients) offering digital business solutions. When asked to talk about those times, he writes back: “It is a very long story, starting with youthful dreams and passions to end up in a fight for survival, success which came years after and defence against people with panda morality or no morality at all. And all of that interwoven with life problems, mutual help, simple friendship. Even when conflicting opinions and their consequences occurred”.

However, he refuses to elaborate.

Still, he is quite correct. Even as we discuss the business side of CD Projekt, stories of dreams, life problems and conflicting opinions are interwoven. Particularly when the company enters a largely unknown territory.

And it is what happened in 1999. Interplay gets persuaded to release its brand new hit, Baldur’s Gate, in Polish. Not outright and not really enthusiastically. Contracts between the game maker studio and the main publisher specify in advance the number of language versions to be implemented in the game. Each additional language version means extra fees due from the main publisher to the studio. So, the Polish version basically stands no chance of being made, let alone break-even.

And so, CD Projekt has to assume the whole responsibility for localisation. And if that wasn't enough, Interplay wants a sales guarantee for no less than three thousands boxes. They put all the eggs in the basket. CDP implement the translation in the game’s code by themselves. Marcin Iwiński pulls the strings of his film maker father and rushes to attract the most widely known names and voices of the Polish film world. In order to encourage the actors, they offer quite substantial sums for those days. Consequently, the artists start enquiring about what computer games are and what localisation work is about, but in the end they say yes. The investment in the game’s Polish version totals 100,000 zloties [25,200 dollars].

“Nestled atop the cliffs that rise from the Sword Coast, the citadel of Candlekeep houses the finest and most comprehensive collection of writings on the face of Faerûn”, so starts the game prologue read by Piotr Fronczewski with his velvety voice.

“Baldur’s Gate” came out in Poland half a year after the world premiere. A huge box with a book, a map with a wax seal, very thick manuals and five CDs for 150 zloties [38 dollars]. It turns out the pirate version is something around 100 zloties, but people prefer to pay more and have an original. It is on the first day that the company sells 18 thousand copies of the game.

CD Projekt has to rent an external warehouse. All editions and add-ons included, the game exceeds a circulation of 150 thousand copies in total. “It was important for the game to be released in a CD format. At a time CDs were still expensive for the Polish buyers, however, they would be increasingly widely spread and started supplanting floppy discs”, emphasises Kosman.

The success of BG gave the executives of CD Projekt food for thought. They knew money would only come with investments. It was Piotr Nielubowicz that made the young businessmen realise the financial side also must be taken care of. He joined the team and started sweeping clean in financial terms. And he is until today.

Starting with the company’s main office. The first office in Wiejska Street in Warsaw, a flat rented for free from Michał's friend, they replaced for a slightly bigger one in Marszałkowska Street. “In such old commie-style blocks. There were very long and low rooms, all crammed with big boxes. When I went up the stairs, I had to bend my head, because the ceiling was so low”, recalls Tadeusz “zooltar” Zieliński, a journalist and games author, today with Nova-Tek/Red Square Games.

But these premises turned out to be not big enough, either. At such a moment today, a start-up would be looking for a co-work to rent in which a neat and nicely exposed office with access to a conference room and coffee (barista coffee, of course), plus Friday sushi maybe, included in the price. Whereas CD Projekt moved to warehouses in Jagiellońska Street. Twenty years ago, Warsaw's district of Praga, the outskirts of it basically, did not have the industrial hipster look of a neighbourhood of communist descent. It is ugly and situated far from the city centre. What counts is the price and the fact that the old building which used to house some warehouses and offices has a potential to rent more premises if need be.

After a dozen years or so, Warsaw (and even Europe) was not enough for them anymore. They opened up an office in “Silicon Beach”. That is the name of a somewhat start-up-, strongly surfer-style of Venice Beach. But before they had a chance to go to the sunny LA, they had to step back in time a bit to the blue-collar Łódź.

“Baldur’s Gate” not only sharpened up CD Projekt’s appetite, but most of all, it opened up the gate showing that Poland does have potential to sell digital entertainment legally. The dot-com bubble has only just burst worldwide, but the writing is on the wall that in 21st century computers, games and the Internet will spread on such a massive scale, that there is an opportunity for some decent business to be made.

Initially, the company makes an attempt at localising “Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance”, which is not a typical RPG and is only to be released for console. “Polish localisation for console, no one has ever done it before. CDP has bitten off more than they can chew! Anyway, they would rehash the story of aiming straight for K2 later on, too”, says Kosman. But in fact, their K2 was still not much higher than our home Rysy at most. The team which localised BG DA soon got a much higher mountain to climb.

In 2002, one of Warsaw’s restaurants hosted a meeting during which a plan was announced: CD Projekt wants into dev. Enough of game publishing, translating and selling alone. It is time to have your own game, and preferably at a world-class level right away.

As the search for a new game concept is on, a new team is also in the process of forming. CD Projekt Red starts off in Łódź, a big industrial city situated 140 km away from Warsaw. There is one reason only: Sebastian Zieliński. He becomes the project’s head and Łódź is where he lives. The name and the logo of the new entity also derived from Łódź: a blue-collar city with red-brick factories. “From the very start I had no doubt Łódź was a better place than Warsaw to produce games”, says Zieliński in “Gazeta Wyborcza” daily in 2002. In his opinion, there are more talented graphic designers and programmers than in the capital. You can apply by mail via cdprojekt.info. Sounds like quite a recruitment process. In fact, it is a team of four. And with this much-less-than-numerous a team, they have a year to make a game.

There is only one thing for sure: the game will be set in the world of Andrzej Sapkowski’s books. “The outlook was not that rosy at all. Sapkowski’s books were widely known indeed, but it was in Poland and rather among his fans. A feature film starring Michał Żebrowski (a popular actor) as the title character fell flat. Metropolis, which was the first one to approach the “The Witcher” as a game, did not make it, either. But people certainly shared a great desire for such a game”, recalls Kosman.

And this is where the troubles began. Initially, the game was to have been released before Christmas in 2003. Over time, however, the Warsaw people were growing more and more suspicious that something in Łódź was not just right. As the outcome of the works was presented, a decision was made: enough with the autonomy, all the works will move to the Jagiellońska hub.

Stoisko CD Projekt podczas targów E3, będące tak naprawdę częścią ekspozycji BioWare, rok 2004. Źródło: i.imgur.com

The decision paid off. Just like the contacts made through hardships at the fairs every now and then - with Greg Zeschuka and Ray Muzyka, which is, the founders of BioWare. Thanks to them, CD Projekt got a cubbyhole of sorts at the great gaming E3 fairs in which they could present a demo of the game they were making.

Still before “The Witcher” was released, it received a few dozen awards. The entire Polish market was waiting as if for a messiah to lead the video games onto a wide international scene. The emotions are so high that the company from Jagiellońska Street would have probably raised the entire release budget necessary from their fans if crowdfunding has been an option then. And they could have probably done with some as CD Projekt was on the edge of insolvency a year and a half into the premiere.

Years later, Iwiński would mention many a time that as they started “The Witcher”, they had no idea how to make games. Over the five years there were “a couple of situations we didn’t know if we would make it till the end of the month”. But when the game was released, it was obvious the effort paid off. In Poland, 35,000 people bought it within the first three days only. And since the way up was packed with abysses, sudden avalanches, and the company made it anyway, CD Projekt’s desire for more and faster only grew.

What may seem today to be of pivotal importance, is the release of “The Witcher”. However, things were happening in the background. Something no less important for the company and its business image. Game producers in those days were at the mercy of global publishers who would try to force minor developers into not necessarily favourable contracts. Including the assignment of rights to the game. Big companies had long deluded the owners of CD Projekt. They were invited to offices for presentations, asked about progress. However, any time they tried to get down to business, things got complicated. Finally, they signed a contract with Atari. As Michał Kiciński recalls while interviewed by “Puls Biznesu” daily, they pulled it off, because Marcin Iwiński put Atari up against the wall: either you sing the contract and announce it or CD Projekt announces the game will only be released by the local distributors.

The relationship with Atari did not run smoothly, though. Immediately after the premiere of “The Witcher 2”, the Polish company removed anty-piracy protection. They claimed it could be broken by the pirates anyway, while only comes as a nuisance to the legal customers. However, Atari did not understand why, instead of chasing pirates, the Polish company only goes along with them. It ended up in a lawsuit against CD Projekt and a compensation of 0.8 million dollars. Plus, high court fees on the top of it. The judgement was a clear sign for Kiciński and Iwiński: you have to be as independent as possible.

The Polish company was convinced that, unlike the western firms, it understood who real competition was on markets like ours. Not other publishers, developers or distributors. Only the pirates. But this kind of competition they did not want to fight all out, only use a trick.

When Michał Gembicki came to work with CD Projekt in 2006, the gaming sector was still fledgling. “CDP at that time was actually more of a book or a DVD film publisher than a gamedev company. It was a company which primarily distributed goods and released games following a license model. It had a huge physical warehouse full of goods, a central sales department, area representatives and a powerful department for the production and marketing of games in the physical form: pressing, printing manuals, text, correction, choice of graphics, description on the back of the packaging”, recounts Gembicki.

“Premiere games were expensive, more than 120 zloties [38 dollars], which was much given the Poles’ purchasing power. Plus, they had a short life cycle. What the shops didn’t sell, would be returned. If you didn’t make it for the release, you had no chance to buy them”, recalls Gembicki.

CD Projekt came up with a idea how to prolong games’ lives. Once returned, the premiere games would be repacked and sold as re-editions in second-hand circulation. Those highly rated by the players and media, as Platinum Collection for 59 zloties [19 dollars], those with poorer rates as Nice Price for 39 zloties [12 dollars]. Six to eight months later, the games would be moved to the cheapest category of Extra Classic for 19.90 zloties [6 dollars]. “This transition from a premiere big box to a small box in the following cycles not only massified the legal sales, but also made it possible to market the titles on a continuous basis’, explains Gembicki.

What’s more, it is these sales that actually generated the lion’s share of CD Projekt’s revenues and made it possible to finance “The Witcher” at all.

But only up to a point. Because a new revolution begins and this time it is not CD Projekt’s products that come as its symbol.

It has for long been apparent that the “box-based” distribution is a model which goes down in history along with the 21st century. The Internet is getting faster, with new services, like Stream, emerging. They turn the business model for selling games upside down. CD Projekt decides to make their own file platform.

At the same time, “The Witcher” is being developed and it is just a tiny bit easier this time. Developers and distributors believe that games with DRM, that is, anti-piracy protection, should no more be sold. And this belief underlies the emergence of Good Old Games (gog.com). And that it will not be a nod towards pirates, but the already mentioned, cunning way to fight them. The following months pass by as increasingly more game producers are persuaded into entering the platform. All of them say “no”. “Finally, we managed to persuade Interplay, which was a very good starting point for us, because they had many classics, such as “Fallout 1” or “Fallout 2”. However, that was a long process and we had a deal only just before the launch”, says Piotr Karwowski, the co-author of GOG, with CD Projekt since 1998.

In 2008 GOG starts off, but it is not the end of the problems yet. The puzzling complexity around the copyright is such that in order to gain the copyright to Activision’s games, the company has to open an entity in the US. Some negotiations go on for ages. Even though, in 2010 GOG sales exceed six million copies of games, out of which half comes from the US and barely 3% from Poland.

In addition to the profits from the platform alone however, it was crucial to build a loyal fan base around it Even more than that - some genuine acolytes. In the autumn of 2010 the site went down for a few days and even a message came out that GOG ceased its operations. It turned out to be just a marketing trick before a new version of the platform was released. Instead of getting angry, the customers took it all lightly. What was of help probably, was the fact that at the launch of a new version Marcin Iwiński and Guillaume Rambourg, the managing director, were disguised as monks to repent their sins.

Today, there are over 4700 products available at GOG from over 600 game publishers and producers, including Activision Blizzard, Bethesda, Disney, Electronic Arts, Ubisoft or Warner Bros. And the platform's sales revenues reached 343 million zloties in 2020 [88 million dollars]. With 162 million [42 million dollars] a year before.

These monk dress-up plays, brilliant press ads were but a prelude to how CD Projekt grew increasingly bold in using modern marketing. That's what the investment in Gram.pl portal and Gram.tv, a tv show, was for. The truth is, Gram.pl was also an on-line shop with games, but it sold barely five to six thousand copies a month. The advertising component was crucial. All the more that it was truly innovative.

“For three years we would be recording a show and I didn’t have the slightest idea that CD Projekt was the partner, or even the creator and the sponsor of it. Really. No idea at all”, insists laughing Marcin Sońta, today’s journalist of the Poland-wide Radio ZET, very well known for his morning show. Since 2006 he had been one of the presenters and the screen writer of Gram.tv aired on TV4. “There was no indication that would have made us think CD Projekt was behind the whole project. And yet, that was quite an investment for a company which was, at that time, a very important distributor, but nothing more than that”, recounts the journalist.

That Sońta knew nothing about his show’s silent partner is less surprising when you look at what was going on around the company's structure at the time. A small firm was transforming into a genuine holding. There was CD Projekt Red which, following “The Witcher” and takeover of Metropolis, set about creating part two of the games on Geralt of Rivia. At the same time, the “big” CD Projekt was in charge of distribution. GOG controlled by Porting House Sp. z o.o. was registered in Cyprus, a tax haven for companies. CD Projekt Localisation Centre was responsible for recruiting programmers for localisation projects. CDP also invested in its subsidiaries in the then Czech Republic and Hungary. The structure got so complicated that a CDP holding company had to be established in the group of CD Projekt.

And then, all the news stations were hit by an event which activated a domino effect leading to an economic crisis in decades.

The bank Lehman Brothers goes bankrupt.

2009 was to be full of success with “The Witcher 2” being released and a stock exchange debut. However, the economic crisis almost totally cracks the company up. Not only because the customers save up on entertainment. They have overinvested, Distribution in Poland and the then Czech Republic, in Hungary. They even had an idea to buy a company in Russia. And like it wasn’t enough, they also signed a contract on “The Witcher” for console with a French developer team which fell through, but they sucked the money out like no other.

The effect is: you have to rescue anything you can. CD Project lay off a large part of the team. From 300 people, a little over 100 remain. They close down their foreign subsidiaries and the localising company. This is what one of CD Projekt’s former employees says about the time back then: “Not many of us remained and we had a meeting with Adam Kiciński who would be very straightforward: ‘this month we don’t have enough to pay salaries’. Everyone was afraid of the last day of the month. It was always such a ‘night of the long knives’. If you don’t get fired on that day, you have a peace of mind for a month to go.

Not the executives, though. “The Witcher 2” left undone. Just like with part one, there would be problems and delays, but once completed, it could get the company back to its feet. Except there was not money to complete it. Venture capital funds the executives talked with did offer financial assistance indeed. However, 90-95% of the company’s shareholding was the stake.

“It is sometimes about a chance in life and such a chance did appear”, starts his story Zbigniew Jakubas, the president of Multico Group and one of the richest Poles in years. In 2010 he was the main shareholder of the then resilient Optimus company taken over with BRE Bank from Roman Kluska. Onet, the largest internet portal and a part of Optimus, was sold to ITI. There was no more business rationale behind Optimus making computers as they were supplanted by China. Still, the Optimus brand remained a value. But there was no idea how to make use of it.

Quite unexpectedly, on the last Monday of September 2009, the idea came to Jakubas itself. Disguised as the whole management board of CD Projekt. Michał and Adam Kiciński, Marcin Iwiński and Piotr Nielubowicz, finance director. “They had an urgent request. One of the commercial banks terminated their loan and they had to repay 12 million zloties [3 million dollars] within three days. Plus, they needed 2.5 million zloties to complete another game. At that time I was totally ignorant about games. Anyway, I don’t know much today, either. But there you have four young and modest people standing in front of you, devastated by the bank’s decision which could destroy their lives’ work”, Jakubas recalls in an interview with us.

The businessman offered to visit the company’s office the very same day and then to think if he wants to invest in it.

“There were harsh conditions. They employed less than 200 people, IT people, graphic designers doing some fixing. I walked through the entire floor where they worked and they didn't even lift their heads from the screens. Typically, when there is a person from outside around the company, it draws people’s attention. And I felt a grenade could go off there and nothing would happen. That really captivated me. It turned out that the people, faces pale from the screens, would work for months for some peanuts and wait for a success to come. Even the board people would not be taking their salaries then”, says the investor.

“I still don’t know what you are doing and I will not pretend I am knowledgeable about it. But your people’s work captivated me. If they believe in the game and are capable of working for a minimum pay, there is nothing more for me to do than to help you”, said Jakubas after the visit.

It may sound like “Business Revolutions” in which Jakubas crops up to change the fate of shiftless start-up people. But in fact, it was a clever business move which was supposed to favour the president of Multico, too.

Jakubas proposed that CD Projekt and Optimus merge. The agreement was as follows: CD Projekt will pay with its own shares (around 78%) for 35 million new shares of Optimus. And for the remainder of the shares, they are supposed to get a cash injection from Optimus. Twelve years ago, Optimus’s share capital was 28 million shares, so the company of Iwiński and Kiciński took control over it. It was about a cunning move: reaching the Warsaw Stock Exchange on Optimus’s coat-tails. In this way the Reds could be listed and Jakubas put up the company’s capital with 14.5 million zloties [4.8 million dollars]. The company was saved. With a portion of this amount, the president of Multico took up 7 million shares per 1 zloty each.

“Did I withstand the pressure and waited until the value rose at least to 100 zloties? No”, admits Jakubas, laughing softly. “Sure, I could have stayed on the stock exchange, reaped the benefits and retired, but in that event I would not have invested anymore. If I had held out until the end of last year and sold the shares at 400 zloties [104 dollars], I would have been top three richest Poles doing nothing. But I made an exit when the shares were slightly above 7 zloties. I needed capital to buy premises from FSO. And, frankly speaking, I don’t regret that, because in this way I received the funds for investments which today materialise as, among other things, a modern housing neighbourhood of “Bulwary Praskie” in the Warsaw district of Żerań”.

The premises purchased with the money are located downright a few hundred metres away from the main office of CD Projekt.

Until the release of “The Witcher 2”, the distribution of games was CD Projekt’s core business. However, as the company entered the stock market and the subsequent parts of “The Witcher” took off, the situation began changing dramatically. The executives found it was the time to stand on their own feet.

The first one was CDP Red, a games producer, and the other GOG.com selling the games in digital form globally. “Meanwhile another big company, CDP.pl, was in charge of distribution. With its complicated business model, a heavy warehouse and local business it represented no added value versus the two”, recalls Gembicki, who was already a key manager at CD Projekt. And he goes on to explain: “Distribution operated on a market which doesn’t understand games and doesn’t love them There's no denying, sentiment for games in retail is just like that for, say, coffee filters. People with passion, love for games, who were very emotional about them, would go to a business meeting with sales people who reduced the commitment to heartless talking about plastic boxes”.

For a while, they would be searching the market for someone to take over. But it dragged on and on. “The reason was the ‘right of return’, the bane of all publishers. The risk was that networks such as Empik or Media Markt could return a few months later as many as 100 percent of the products they took. Based on a simple excuse: ‘well, it didn’t sell’”, recalls Gembicki.

For legal restraints, you can't call this model “consignment”, but in fact, it would remind of consignment at times. On the top of all that - payment deadlines of 150, sometimes even 200 days.

Negotiations on taking over the business by distributors, particularly IT, fell through, too, Selling games is about something else than the distribution of equipment. And then, an idea was voiced for the company to be taken over by its managers. That is, for the distribution part to be separated and bought out to make an independent business. “I don’t know if I would be tempted again, but at that time it was a super deal. I already had the experience with CD Projekt, we survived the crisis of 2008. I didn’t want to lose control and I hoped that by engaging in the purchasing process, I would keep my job and the company”, recalls Gembicki.

Gembicki calls the process “a split of convenience”. “Together with Robert Wesołowski we managed to come to terms with the management board of CD Projekt. It seems it was a satisfactory split for the parties concerned. The Reds could get rid of the tasks that weighed them down, whereas we could become independent and focus on our individual plans. I felt I was treated very much like a partner in that situation and I took the risk in full awareness. Although my position was hard as I was actually an employee negotiating my future with the employer”, he recalls.

The new CDP.pl released “The Witcher 2” for xbox and “The Witcher 3” for all platforms - on their own, still in close relations with CD Projekt.

“Anybody with a sharp judgment of the situation knew that the market of distributing boxes was on the decline and you had to leap into the future. Gembicki and Wesołowski spared no effort and they sought support on the market, but the growth in digital distribution showed it would be difficult to do something about it”, Radek Zaleski, a former development director at CD Projekt, recalls. He calls the spin-off of CDP a pivot attempt of sorts: “The plans pulled through only because CDP was transformed into a typical e-commerce”.

Much as in its early days, the plan was even braver. “Download as easily as at chomikuj.pl [a file hosting service], pay as if it's Allegro [an e-commerce platform]”, such was the idea of what CDP.pl was supposed to be. “My task was to launch CDP.pl for a given date. There was pressure, there was an order, so we had to snip and reduce some modules. There were still very few games, but we were going to launch big, with live streaming anyway, because it would be good marketing-wise. This is what the company does at all times, and I do respect it”, says Radek Zaleski. On day “zero” he appeared on stage and kicked off CDP.pl like Steve Jobs showing the first iPhone. The interest was so that everything crashed, of course. “But the objective was achieved. Techland also built a digital distribution platform later on, but because they didn't make such a fuss, nobody talked about it”, emphasises Zaleski.

Finally, Gembicki and Wesołowski took over the whole of CDP.pl in 2014. What the company started and made to the top with, which is, CD trade, pretty much disappeared off its radar.

The atmosphere is great, because much as the release of “The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt” is traditionally delayed, it turns out to be not so much a success, but a spectacular success. As early as a week before the premiere, the pre-orders amount to a million copies. Three and half a year of work and a budget of more than 306 million zloties [100 million dollars] will break even with no major issues as early as in the first year. What is more, even today the game is a cash cow. A total of 28.3 million copies of the game have already been shipped to customers over the five years following its release.

The company becomes a global player. “Tsehdeh Proyekt” - Iwiński makes sure, however, that even abroad the name is pronounced in Polish. And as he addresses the following questions, he talks about the Slavic unrepentant soul. Not only of Geralt, but also the people behind the company.

In 2018 Piotr Nielubowicz, the vice-president, reports that thanks to a global trend and rising digital sales, the company expects a margin on the sales of an single copy to be higher even by a few percentage points. “The Witcher” itself also switches from boxes to the digital. According to the company’s most recent financial statements, in 2020 the digital editions already account for as much as 84% of sales, although it was barely 30% in the first year following the premiere.

The company from Jagiellońska Street is investing again.

In people. Between 2014 and 2020 the headcount grows from 400 to almost 1200 persons. The company also attracts increasingly more employees from the world: in 2019 it is 256 persons, that is, 23 percent of the team.

It invests in developer teams for which studios in Kraków and Wrocław are opened. The latter team is formed in 2018, following an investment in an already running company, Strange New Things. A moment later the Reds also take over Spokko, a developer studio which specialises in mobile projects.

And, increasingly more, in marketing. After all, it was as early as in 2012 that Iwiński announced that the company, particularly its most advanced and experienced developer teams, were working on a brand new product: “Cyberpunk 2077”.

And when Keanu Reeves appeared on the stage at E3 fairs in 2019, during a demo of the nearing game, it was a breathtaking moment not only for the fans, but primarily, the investors.

CD Projekt is on everyone’s lips. And drives the entire Polish market. “It is definitely on the wave of “The Witcher 3” popularity that the Polish gaming got a major boost and a lot of accessible capital emerged around it. It is often so that something merely subsuming gamedev will do to enter NewConnect stock exchange”, says Michał Bobrowski of GRY-Online SA. Today, fifty-six companies which maintain they operate on the gaming market are quoted on the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

CD Projekt itself is not losing momentum, either. The more its shares rise, the more often voices are being heard from the deep inside of the company that this time, it is not just about climbing K2. It is a fight for the world summit without oxygen on top of it. Subsequent postponements of "Cyberpunk 2077" release dates, management officially admitting that employees need to crunch, and finally the long-awaited premiere. Only that instead of a spectacular success, a wave of players’ complaints, apologies and promises of fixes followed.

An overinflated balloon bursts out with a bang. And so does the stock market bubble.

The valuation of the company at the record evaluation of 450 zloties [115 dollars] per share reached almost 47 billion zloties [12 billion dollars]. The numbers plummeted over a few months. Today, the company’s valuation is around 18.7 billion zloties [4.8 billion dollars] and the price slightly exceeds 186 zloties [48 dollars]. And if that wasn’t enough, beginning 2021 the company got at the forefront of investors’ focus. Investors who do short selling. Quite particular investors, because some short funds would also sell long while, at the same time, minor revolutionary, yet organised players would sell short, as was the case of GameShop. Consequently, the Reds’ price jumps around like crazy over a month.

Zbigniew Jakubas, a millionaire, makes things clear: the so-called short sale of CD Projekt’s shares by American funds is but a huge gamble. People tended to treat the official editions as special collections for enthusiasts, hence the expectations were higher than those for pirate stuff. It is publishing series that unleashed mass sales of legal games in Poland and changed the market beyond recognition.

“No company must take responsibility for such irrational behaviour of investors who pump one another up and pump the price above and beyond. You can just as well go to a casino and make your bet on red or black. Those who are now trying to sue the company behave as if they went to a casino, lost and now they accusing the casino of their losses. Someone would have to prove that CD Projekt actually falsified or hid the data for the claims to be sound”, says Jakubas.

A real roller-coaster rally begins. Elon Musk twits that CD Projekt is incredible, the shares jump up. Sony withdraws “Cyberpunk 2077” from PlayStation Store, they go down. The company releases patches with fixes and the price is up again. And what is missing from the frenzy around the Reds is only a hacker attack. Which not only sends the stock market wobble again, but it also attracts investigators and controllers to the company. Plus, threats of lawsuits for deliberate manipulation of the stock market.

We asked all of the fifteen American law firms which announced it in January that they were awaiting claims from the harmed investors by end February, how much evidence they managed to collect and how high damages they want to fight for.

Some of them fobbed us off saying that the procedure was still at an early stage. But the majority of them fell silent. In its annual financial statements, CD Projekt itself makes no mention of whether they have the funds to cover the costs of court cases or damages, if any.

But they have the budget for 2020 bonuses for the board members. The company’s five top managers have just become richer by a total of 120 million zloties [32 million dollars]. Almost ten times as much as they needed a decade ago to save the company.

Publisher: Jakub Wątor

Authors: Sylwia Czubkowska, Jakub Wątor, Marek Szymaniak, Matylda Grodecka

Photos (in order):

Commodore and floppy disks, Michał Kiedryna;

„Baldur's Gate”, (press);

CD Projekt Red, Ryszard Chojnowski;

The Witcher 1, 2 & 3 (mat. prasowe);

CD Projekt HQ (fot. Grand Warszawski / Shutterstock.com);

Poznań, Game Arena, 2014 rok (fot. Wikipedia/klapi);

Cyberpunk 2077 add in front of CDP HQ, 2021 (fot. MOZCO Mateusz Szymanski/Shutterstock.com)

Najnowsze

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T11:31:44+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T11:23:48+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T11:10:54+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T10:28:22+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T09:52:12+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T09:28:07+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T09:21:29+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T08:01:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T07:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T06:23:50+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T06:20:28+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T06:15:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-23T06:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T16:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T16:10:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T16:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T09:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T09:10:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T09:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T08:30:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T08:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T08:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T07:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T07:10:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-22T07:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:40:29+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:38:32+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:37:51+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:36:18+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:32:12+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T16:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T12:24:56+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T12:24:11+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T09:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T09:10:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T09:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T08:30:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T08:20:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T08:00:00+01:00

Aktualizacja: 2026-02-21T07:20:00+01:00